Tamita Brown, co-owner of Caribe United Farm, brings non-GMO feed to the chickens on pasture in Crawford, Georgia on Friday, March 25, 2022. Brown raises chickens, guinea fowl, pigs, ducks, and geese on her five-acre property and sells both meat and eggs at market on the weekends. (Photo/ Basil Terhune)

Howard Sanders’ father began poultry farming in the 1980s, shifting away from the family’s previous practice of raising cattle and farming.

Within a few years, they had nine chicken houses on their property in Stephens, and had established one of the most prominent poultry farms in Oglethorpe County.

“There just weren’t that many poultry farms in the county at the time,” Sanders said. “Back in the ’80s, we were probably one of the largest poultry farms in Oglethorpe County.”

Times have changed, however.

The poultry industry has blossomed in Oglethorpe County over the past four decades, meaning that nine chicken houses can’t compare with the large chicken farms of today.

“Now, we’re not even close,” Sanders said.

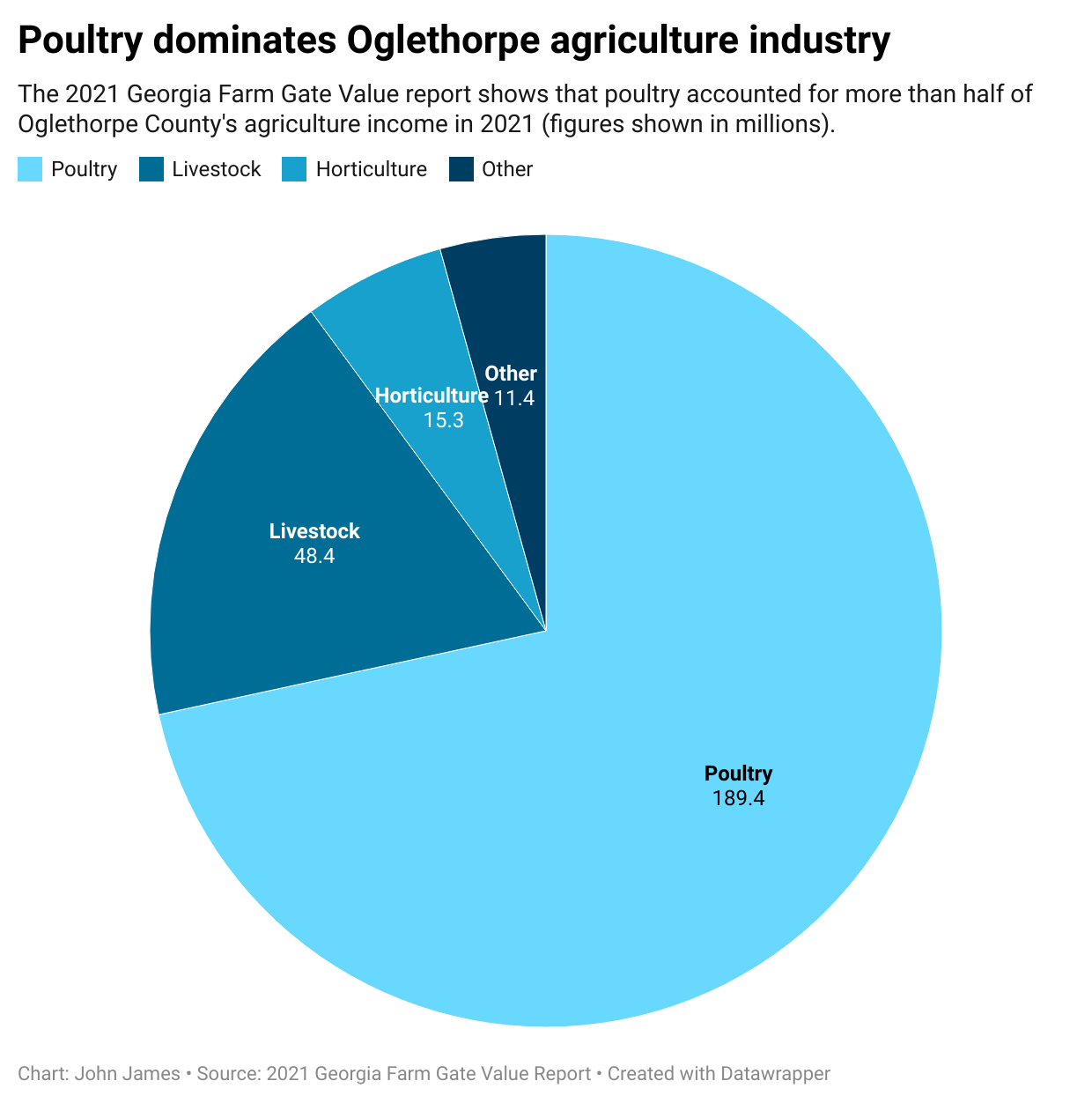

Poultry and egg production was a $189.4 million industry in Oglethorpe County in 2021, according to the Georgia Farm Gate Value report. That was the sixth-highest figure in Georgia and accounted for over two-thirds of Oglethorpe’s total farm gate value of $270.7 million in 2021.

Sanders said the primary reason for Oglethorpe County’s lucrative poultry industry is simple: space. It has maintained its status as a rural county, filled with plenty of open land fit for the establishment of chicken houses.

“We don’t have many major cities,” said Sanders, who also serves on the Board of Commissioners. “Crawford and Lexington are the biggest towns, but there’s still a lot of farmland — a lot of family-owned farmland — here in the county.”

Poultry is also cheaper than other meats, making it an in-demand product. Sanders said there is a large market for poultry overseas, adding even more options for farmers looking to sell their goods.

The immense demand for poultry has also driven “integrators” to invest in poultry farms around Oglethorpe County, Sanders said. He said large companies, such as Pilgrim’s or Harrison Poultry, will reach out to farmers here and offer to support their chicken farms without fully taking over the operation.

“All they do is supply the chickens and the feed,” Sanders said. “There’s not a corporation that I’m aware of that goes in and buys up poultry farms, then takes them over.”

Without the backing of larger companies like Pilgrim’s Pride, some local chicken farms have had trouble keeping up with their more well-connected competition.

For Gabriel Jimenez, the co-owner of Caribe United Farm, the process is the biggest difference between how small farms and large farms operate in Oglethorpe County.

“There are chicken houses where they have 30,000, maybe 40,000 chickens at one time,” Jimenez said. “We don’t do that number. We do chickens outside, 24/7, and we only do like 600 of them … It’s a well-run operation, but the quality of the chicken is different than the one that you get when you’re doing pasture raised. That’s what we do, and it’s different.”

Jimenez and his wife, Tamita Brown, have pasture-raised chickens since they started farming in 2018. Jimenez said it gives the animals a chance to “behave like a chicken,” which isn’t always possible on farms with less space.

Jimenez said the chickens are happier when they’re able to roam, which leads to better meat for the customers. Still, that type of farming can be difficult to manage over long periods of time, especially for small organizations with few employees.

“We have a lot of animals — chickens and pigs and turkeys that we need to take care of, eggs that we need to watch and handle — all this stuff that we need help with, but it’s just the two of us,” Brown said. “We are actively searching for employees, but it’s hard.”

Jimenez said he’s seen several small local farms forced to shut down over the past few years, collapsing under the pressure of high demands and long hours.

Jimenez continually stressed that the poultry industry isn’t for everyone.

“You’ve got to have thick skin to be in this business,” he said. “And you have to work really, really hard to get more customers, because you can be out of business, like, tomorrow. That’s the reality.”