Sonja Thompson Roach remembers the moment last year when a photographer took photos and interviewed her son and his friends for a Time magazine story on mental health and teens.

The photo and interview shoot in her Northeast Georgia home required absolute quiet for the audio and the right time of day for the lighting.

But one thing stood out the most.

She heard her son, August, answer questions about his father’s death from COVID-19 in 2021, giving information to the photographer that would be helpful for other kids.

And Thompson Roach then heard his friends share their experiences being bullied.

She was proud of them for speaking out.

“It’s just so, so revealing, and you want to honor the fact that they’re really trying to deal with all of these things,” said Thompson Roach, who lived in Oglethorpe County and now lives in Hartwell. “And at the same time, really be attuned to maybe the fact that they are struggling with feelings that you really never even scratched the surface of as a parent.”

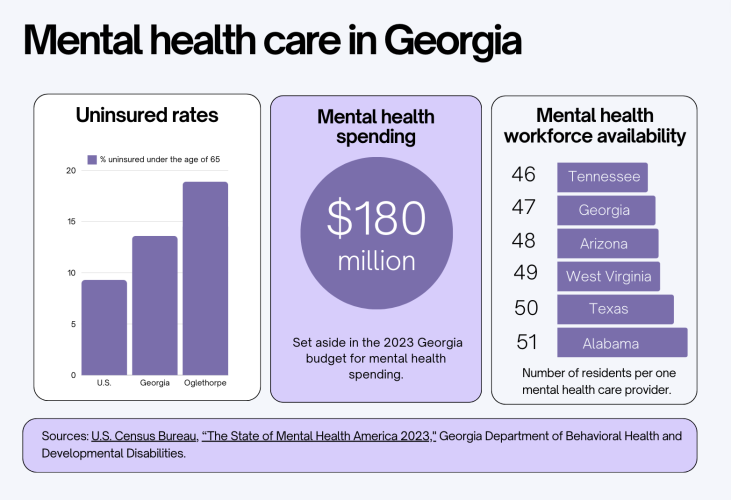

Statistics indicate alarming rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation among children and teens across Georgia and the U.S. Georgia ranks in the top 10 of states with youth with substance abuse disorder (No. 2) and those who experience major depression (No. 10), according to “The State of Mental Health America,” a 2023 report by Mental Health America, a national advocacy organization dedicated to mental health.

Care is particularly hard to come by in rural communities like Oglethorpe County that struggle to provide adequate mental health resources for children and families.

“In rural areas, there are very few providers, and the ones that are, are so restrained,” said Stacie Johnson, who worked in the mental health field for nine years as a counselor before becoming an advocacy coordinator for the Northeast Georgia Court Appointed Special Advocates.

With 15,469 residents spread over 442 square miles, Oglethorpe County — like other rural communities — struggles to attract health care providers. They are reluctant to set up practice in an area where families must travel long distances to access their services, which they may not be able to afford.

An estimated 12.7% of Oglethorpe County residents live in poverty, according to 2022 U.S. Census data, compared to the national rate of 11.5%.

Due to shortages of mental health care workers and limited health care coverage, the rate of uninsured individuals in Oglethorpe County under the age of 65 is double the national average, according to Census data. Many families rely on schools to fill the gaps.

Turley Howard, the Oglethorpe County School District’s social worker for a decade, recognizes that almost all the resources available for mental health services in Oglethorpe County are through the school, but that doesn’t intimidate him.

“To me, one of the best parts of my job is getting inside the lives of people, and be allowed to know what not everybody knows,” he said. “And to me, that’s a giant privilege. It's a huge responsibility and privilege.”

He said he believes the combination of school and community resources are capable of providing service to everyone in need.

“A lot of times, we involve other people,” he said. “I tell people all the time, ‘Come to me, if I don’t know how to help you, I’ll try to find who … can do it for you.’”

Connecting students, services

The Oglethorpe County School System has five school counselors, one wellness counselor and one social worker for 2,322 students.

They rely largely on referrals from teachers, parents and other community members to know which students they need assistance. For more serious or long-term problems, counselors will refer the student or family to external resources, usually private practice therapists in Athens.

“It’s like a family,” Howard said. “People really look out for each other.”

Thompson Roach retired from the Oglethorpe County School System in 2011. She said she had talked to school district officials, who are considering using the videos conducted for the Time story to talk to kids about mental health.

She said one of the people who saw the story told her, “This is big, thank you for those who stood up for themselves at the same time for speaking out for those who have not had a chance to speak in this way.”

Even with several resources in place, many families face difficulties with transportation. The schools work with different agencies, such as Project Family, the Social Empowerment Center and Pathways, to connect students with therapists who come to the school for sessions during the school day.

These agencies send therapists to Oglethorpe County to meet with students at their school for 30-45 minute sessions, alleviating concerns about transportation or time management.

“Those counselors are hustlers,” Howard said.

Oglethorpe County Schools use efforts like Oglethorpe County Elementary’s mentorship program and monthly guidance lessons.

Katie Edwards, the elementary school’s counselor, said she talks about topics like empathy, anxiety and self control. She plans lessons that vary by grade level and visits every classroom to present them.

As the only counselor at OCES, Edwards said her schedule is often put on hold to address students’ more immediate needs. She said while “some days might be harder than others,” she knows the students are grateful for their teachers’ and counselor’s help.

“I get a ton of hugs every morning,” she said.

Additional assistance

Oglethorpe County’s schools also have a partnership with Advantage Behavioral Health Systems through the state’s Apex Program, which has received a boost in funding and aims to “reduce the number of youth with unmet mental health needs,” according to its website. In the past four years, the majority of schools within the Apex program come from rural areas.

David Kidd, board chair and Oglethorpe County representative with Advantage, said being so closely connected with the school system also allows Advantage — one of many state organizations, called Community Service Boards, that provide mental health services — to establish a broader reach across the county.

“You might have a teacher or a parent refer a student to the clinicians, and very often from that, they see a broader spectrum of people within that child's family background,” Kidd said.

Miriam Shook, who works with Oconee County Schools and was appointed by Gov. Brian Kemp to the Georgia Behavioral Health Reform and Innovation Commission, said she has seen how the community and school systems serve those in need.

“While the school system does provide solid services for people in need of mental health services, the counselors, school social workers and community liaisons are a wealth of knowledge and information, connecting people with resources and following up on a variety of needs,” she said.

Identifying needs, lack of access

Advantage serves what the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services identifies as a high needs Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA), which encompasses Oglethorpe County.

Laurie Bailey, a director of clinical projects at Advantage, said it primarily helps individuals who have no form of federal or private insurance, acting as a “safety net provider” for the counties they serve. Advantage works on a sliding fee scale and adjusts the cost of services based on the patient’s income level.

However, the closest Advantage clinics are in Athens, making transportation a significant barrier for some Oglethorpe County residents. Additionally, many residents also lack funding for the commute or are unable to create time within their schedules to seek out services, Bailey said.

Oglethorpe County Emergency Medical Services Director Jason Lewis said transportation issues leave many patients resorting to the emergency room, the closest of which also is in Athens, for mental health services.

“The ER ends up being that catch all,” he said. “That safety net.”

Lewis said Oglethorpe County EMS is “grossly lagging behind” on appropriate training and services for mental health crises. Transit issues and a limited number of ambulances don’t help.

If a crisis happens in the middle of the night, when only two ambulances are running, Lewis said EMS response can take hours. This also means one call could occupy half of Oglethorpe County’s ambulances for that time.

He said Athens Clarke-County has a team that includes social workers and mental health counselors who help respond to calls where mental health is a factor. He said “we would love to be able to do something like that here,” but the county may not have the volume of calls to support the cost.

The Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities provides funding for Advantage to arrange transportation for uninsured patients in Oglethorpe County. However, the department said that due to time delays, this isn’t a perfect solution and it sees the impact of a shortage of behavioral health care workers throughout the state.

Bailey said lack of local resources can also hinder residents’ awareness of the behavioral health services accessible to them.

“That issue is compounded when you don’t have a bricks and mortar site in a county,” Bailey said. “I don’t think that everybody who needs the services even knows that we’re here.”

In another effort to bridge the gap created by limited transportation, many organizations have turned to telehealth services.

However, those can be inaccessible in rural areas like Oglethorpe County.

According to the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, rural counties face the unique challenge of having limited access to reliable broadband internet, so whether it’s due to affordability or dead spots with no reception, it is difficult for telehealth to be a consistent or reliable form of treatment in these areas.

Room for improvement, hope

From the emergency responders perspective, Lewis said the EMS struggles for training is in mental health crises partly due to the lack of continuing education available for emergency responders.

“As, you know, we as a state and we as a country become more in tune with the needs of those that struggle with mental health and addiction, I think we’ll be more kind of in tune to tailor our public safety response,” he said.

Kidd said there is a definite need for increasing statewide funding in order to continue providing and improving mental health care resources.

“There are barriers to all Georgians receiving this just because of the lack of funding for these services,” he said.

Jill Boyd, whose two children attended Oglethorpe County schools and were featured in the Time article, said the “teenagers were very brave to show their vulnerability, and they were even more brave than what most of us adults would be to share.”

“I think it's our present-day culture, in growing more open to talking about mental health, which is good, because I'm in my 40s, and I've only seen this openness to it, and maybe the last 10 to 15 years, that wasn't something that I grew up being exposed to people being vulnerable and talking about their struggles, and often, if people needed to take an antidepressant, you know, they were more secretive about it,” Boyd said.

Boyd, who holds a master’s degree in Biblical counseling, said she noticed that the accompanying video piece in the Time magazine story started with her daughter’s negative, sad and depressing comments, but then balanced it with the teenagers’ hopeful, positive and encouraging comments.

“We're getting better at that, as a nation and a society,” Kidd said. “But … still a major stumbling block to getting people the help they need is the stigmatization of mental illness.”

Cassidy Hettesheimer contributed. This story was written by the Covering Poverty project, which is part of the Cox Institute’s Journalism Writing Lab at the University of Georgia, as part of its participation in The Carter Center’s Mental Health Parity Collaborative. The collaborative is a group of newsrooms that are covering stories on mental health care access and inequities in the U.S. The partners on this project include The Carter Center, The Center for Public Integrity and newsrooms in select states across the country.